Writer Samuel Johnson once said that the next best thing to knowing something, was knowing where to find it.

Of course, in the 18th century when he first mentioned this there was no Google to act as that instant fountain of all knowledge. Perhaps the nearest thing to it was Johnson’s own dictionary of the English language, described as one of the greatest single achievements of scholarship.

But in his day, with no internet, learning more often than not would come from practical, hands-on experience, not a couple of clicks or a You Tube video. Modern tech has certainly made learning easier, but in some professions real life, not virtual, experiences count for so much.

Just look at the next generation of architects who are starved of much needed practical experience in complex building projects. Today’s trend in the housing sector across Scotland is to construct new-build developments. Green field development sites are much more predictable to build, in terms of risk, finance and timing, and therefore enable those targets to be met, but they do little to train architecture students in how to reprovision our current built heritage. Tackling the redevelopment and repurposing of old buildings into new homes is complex and challenging, but it is vital for today’s students to have experience of this, if we are to repurpose what we have and reduce carbon emissions in the sector.

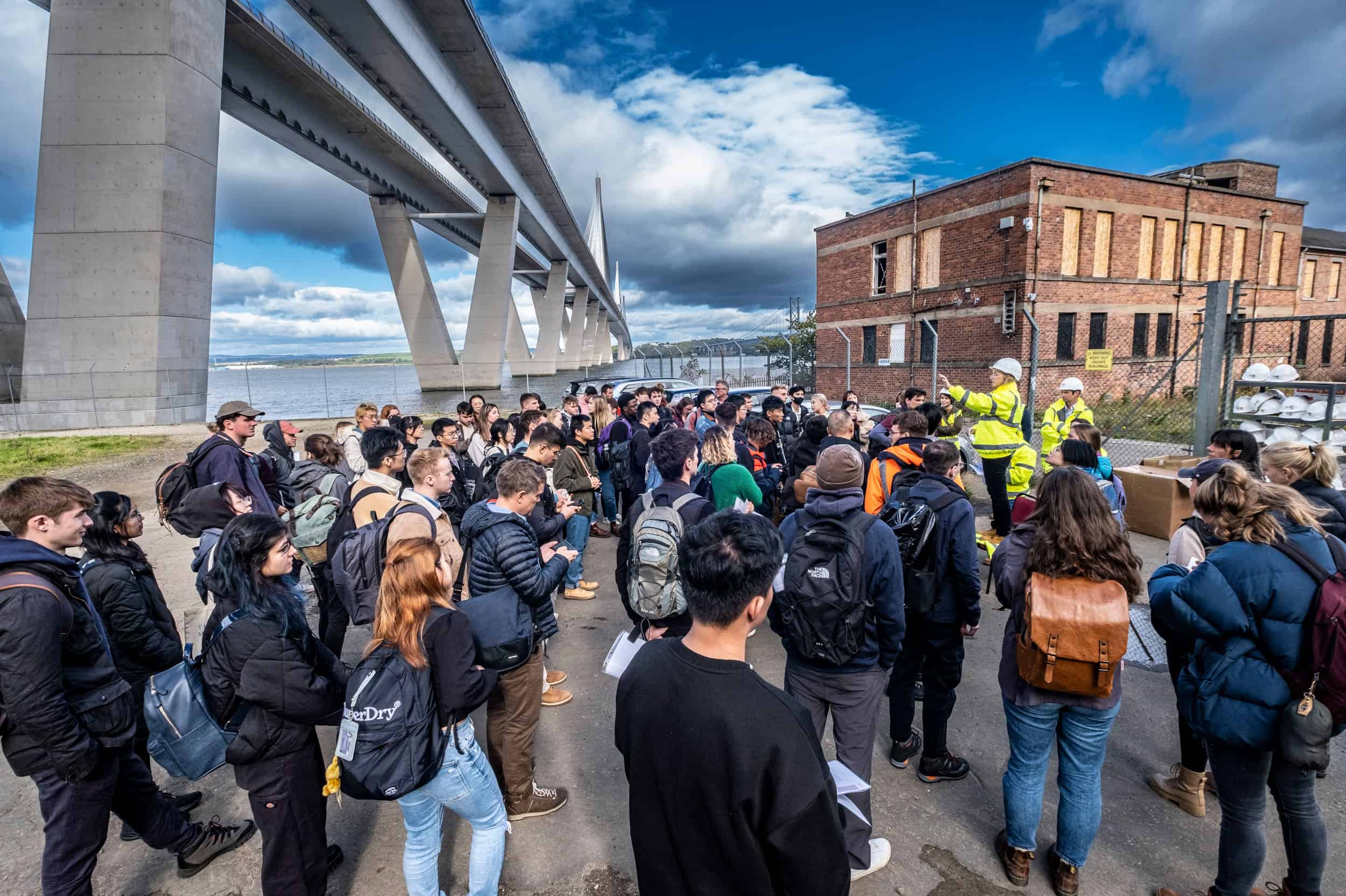

There are, however, some brilliant exceptions, one of which is the development currently underway at Port Edgar in South Queensferry, Edinburgh, of a former naval base. This 16-acre abandoned and semi derelict site, that includes a prison block, a hospital wing, officers’ quarters and living accommodation for the rank and file servicemen, is in planning for redevelopment into high quality homes and community facilities by Lar Housing Trust.

The housing charity has recently welcomed almost 100 architecture students from both Edinburgh and Newcastle Universities to tour the site, take readings and measurements, discuss the challenges with the construction team and study the plans for its redevelopment. Lecturers at both universities were extremely grateful for what they described as a rare opportunity for their charges to see “in real life” such a complex project. Surely a worrying observation that the opportunities to visit more sites are not more frequent?

With the obvious carbon capture benefits of repurposing old buildings, it is anticipated that reuse of our build heritage will be more of a focus for the construction sector going forward. Organisations like the Scottish Empty Homes Partnership (SEHP) have an important role to play in changing mind sets and have already facilitated the restoration and reuse of 8,000 homes through its network.

The inherent risks of tackling difficult developments, however, don’t necessarily fit easily into budget conscious business plans and strict delivery timelines, so the more experience that the students of today can have of these buildings, the better equipped they will be to ensure that (once they are in the workplace) they are aware of (and have met and can deal with) the challenges they will face in reconstruction projects.

Local and central governments also need to think about how to make reuse an attractive proposition to allow and encourage more developers to increase their risk appetites. By doing so, a greater mix of homes will emerge, new life will be breathed into old buildings and architects will be engaged in more challenging projects.